The Problem

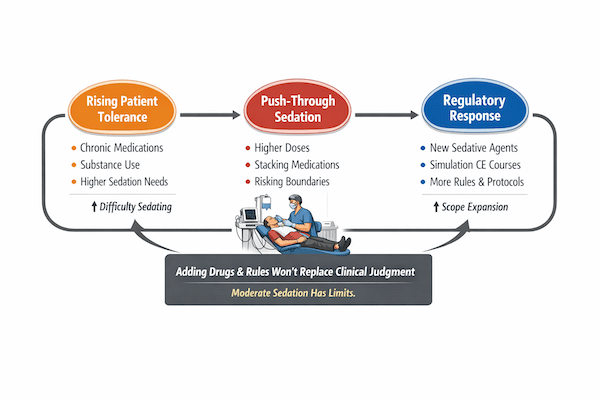

Across American dentistry, particularly in office‑based moderate sedation, a quiet but consequential shift is underway. Dentists, assistants, and regulators alike are noticing that patients are harder to sedate, require higher drug doses, and behave less predictably during and after procedures.

This is not a matter of technique, effort, or professionalism. It reflects a deeper change in the patient population — and it raises important questions about how dentistry responds when moderate sedation begins to strain against its natural limits.

A Changed Dental Patient

The contemporary dental patient arrives with a very different neurochemical baseline than in decades past. Even patients who appear healthy and forthcoming often carry a history of chronic exposure to centrally acting substances, including:

- SSRIs and SNRIs

- Benzodiazepines (current or prior)

- Prescription opioids

- Gabapentinoids

- Stimulants

- Cannabis, often daily and often under‑reported

The result is not intoxication but neuroadaptation: altered receptor sensitivity, shifted dose–response curves, and blunted reactions to sedatives that once worked reliably. Dentists providing moderate sedation are increasingly encountering patients who do not settle with traditional dosing paradigms.

When Moderate Sedation Becomes a Throughput Tool

Moderate sedation in dentistry was never intended to be limitless. Its safety historically depended on a shared professional understanding that some patients — due to anxiety, tolerance, comorbidity, or physiology — simply do not belong in a moderate sedation model.

As patient tolerance rises, however, pressure builds:

- The procedure is indicated

- The patient is anxious or resistant

- The sedation is inadequate

- The instinct becomes: add more

This phenomenon — push‑through sedation — is not driven by recklessness. It is a predictable response in a practice environment where sedation enables higher‑revenue procedures, improves patient acceptance, and maintains competitive parity.

But it represents a subtle ethical shift: difficulty is no longer interpreted as a signal to stop, but as a technical problem to overcome.

The Regulatory Response in Dentistry

Regulatory bodies are not unaware of these pressures. As adverse events and near‑misses related to opioid and benzodiazepine escalation become more visible, regulators naturally seek harm‑reduction strategies.

Common responses include:

- Expanding acceptable sedative agents

- Allowing additional drug combinations

- Requiring periodic emergency simulation continuing education

- Increasing documentation and monitoring expectations

These measures are well‑intentioned and often framed as patient‑safety initiatives. They are attempts to stabilize a strained sedation model without fundamentally redefining its boundaries.

But they share a critical assumption: that protocols, simulation, and pharmacology can substitute for the judgment formed through residency‑level anesthesia training.

The Judgment Gap

Emergency simulation improves response. Protocols improve consistency. Additional agents may reduce certain risks while introducing others.

What these measures do not create is the judgment to recognize — early and decisively — when sedation should not proceed at all.

That judgment is not algorithmic. It is experiential. It is developed through years of supervised exposure to unstable physiology, evolving complications, and the lived consequences of anesthetic decision‑making.

In dentistry, most moderate sedation permit holders are general dentists trained through commercial or short‑format educational pathways. While many are conscientious and skilled clinicians, this training model does not replicate the cognitive pattern recognition and anticipatory judgment that come from formal anesthesia residencies.

This is not a criticism of general dentists. It is a recognition of structural reality.

Risk Displacement, Not Risk Reduction

When regulators respond to sedation strain by adding drugs rather than re‑asserting limits, risk is not eliminated — it is redistributed.

- Obvious respiratory failure may be replaced by quieter hemodynamic instability

- Early warning signs may become more subtle

- Complications may unfold later, when vigilance is lower

In an office‑based setting without deep anesthesia experience, these failure modes may be harder to recognize and harder to rescue — even as the overall approach appears safer on paper.

Sedation Has Limits — and That Matters

One of the core principles taught in anesthesia‑trained dental specialties has always been simple:

There are patients you do not push through.

Difficulty is diagnostic. It is not a challenge to overcome, but information to respect.

When regulatory frameworks implicitly encourage persistence — through expanded drug options and layered guardrails — they risk eroding this boundary ethic. Sedation becomes a means to preserve throughput rather than a clinical judgment exercised with restraint.

Re‑Centering Dental Sedation Safety

If patient safety is truly the goal, dentistry must be willing to re‑embrace uncomfortable truths:

- Moderate sedation has finite limits

- Rising tolerance does not justify deeper persistence

- Simulation and CE cannot replace experiential judgment

- Escalation to general anesthesia is not failure — it is appropriate care

Until these principles are re‑centered, well‑intentioned efforts to make dental sedation safer may paradoxically extend it beyond where it was ever meant to go.

In a changing patient population, restraint — not expansion — may ultimately be the safest intervention of all.